This 3 Valley Vegans newsletter is not our normal periodic one. It’s an important newsletter because it relates to the huge threat to humanity if urgent and decisive action is not taken to avert the worst that climate change will increasingly throw at us. As one of the big three contributors to climate change, the food people eat should be a very important subject for attention. (Transport and the energy used in buildings are the other two big contributors.)

Right now, you will be hearing, watching or reading about the blah blah blah of the COP27 climate change conference in Egypt and its big ag prescriptions of vested interests. At a local level, hopefully genuine commitments to tackle climate change are being made. In January 2019, Calderdale Council took the climate change threat seriously and declared a ‘Climate Emergency’. It followed that up by setting a 2038 target for achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions, the gases causing climate change – mainly carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide.

Call for you to take action

The Council published its Draft Climate Action Plan recently. It’s currently open for public consultation and the period for that ends on Sunday 20th November. I hope that you will want to respond to it because the plan only contains weak aspirations regarding dietary change and absolutely no specific actions to deliver them. Of course, there are other aspects of the plan that you may want to comment on too. Here’s the link to enable you to read it and then submit your comments: https://www.calderdale.gov.uk/ClimateActionPlan

Plants: the forgotten saviours

Calderdale’s Draft Climate Action Plan contains only one action regarding food directly: “Calderdale Food Network: Silver by 2023 and gold by 2025 or sooner.” The silver and gold referred to are awards from an initiative called Sustainable Food Places. There is no information on its web site to explain what is involved in a silver or gold award but it is quite clear that reduction or elimination of animal product consumption is not given a high priority. Calderdale Food Network’s Food Charter is a little more encouraging in including an optional pledge for individuals to “reduce red meat and dairy consumption.” (3 Valley Vegans is now being represented in the Calderdale Food Network).

In your comments, you might wish to question why the Draft Climate Action Plan has not even committed to action related to the diet-related recommendations of the Climate Change Committee (CCC), an independent and statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008. The CCC has recommended to central government: “Take low-cost, low-regret actions to encourage a 20% shift away from all meat by 2030, rising to 35% by 2050, and a 20% shift from dairy products by 2030, demonstrating leadership in the public sector whilst improving health.”

A little more ambitiously, Henry Dimbleby has advised central government, through his independent review of the National Food Strategy, that a 30% reduction in meat consumption would be needed by 2030 to meet the government’s own budget for greenhouse gas emissions, its “5th Carbon budget”. There’s nothing like this or the CCC’s recommendations reflected in Calderdale’s Draft Climate Action Plan let alone what Dr Marco Springmann and his colleagues at Oxford University have calculated as necessary for UK and USA citizens to do to limit climate change to a just-tolerable but still risky level:

- reduce pig, cow and sheep consumption by 90%;

- reduce chicken and other bird consumption by 60%;

- increase legume consumption by 500%; and

- increase nut & seed consumption by 400%.

Source: Springmann M et al; Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits; Nature 562; 519-25 (2018)

The work of Springmann and his colleagues is in stark contrast with a statement in Appendix 2.2 of Calderdale’s draft action plan that red meat (not all meat) and dairy consumption need to be reduced by only 32% by 2038. There is no action in the plan associated with this inadequate aim. It’s worth noting also that the heading to Appendix 2.2 indicates that only an 82% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions will be achieved by 2038 if every aspiration in the entire plan is met. Given that many of the other aspirations are harder to achieve and that the Council is supposed to be achieving net zero emissions (not 82%) by 2038, the draft plan needs to be more ambitious than at present and that ambition needs to be backed up with concrete actions.

In the Land and Nature section of the draft plan, on page 43, second paragraph, there is a claim that grazing by cows and sheep has to continue to maintain Calderdale’s grasslands. What this really means is grazing to conserve habitats as they are at present…even though nature does a far better job of providing greater levels of biodiversity when left alone. The latter is called re-wilding. If Calderdale’s pastureland were to be re-wilded it would be much more beneficial for biodiversity than grazing. It would also take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Harvard academics modelled the impact of a global shift to plant-based diets and established that this would remove around ten years worth of global greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere. Re-wilding is not even mentioned in Calderdale’s draft action plan.

Source: Hayek, M.N., Harwatt, H., Ripple, W.J. et al. The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land. Nat Sustain 4, 21–24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00603-4

Recent research by the University of Liverpool indicates that sheep grazing adversely affects the diversity of plant species in upland areas of the British countryside. It could also take up to 60 years to recover after grazing ceases. Grazing by cows in Calderdale is less common and less harmful to biodiversity than grazing by sheep. However, like sheep, cows’ hooves trample the land and that impairs biodiversity. It also impairs water absorption and increases rainwater run-off.

In addition to missing opportunities to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, the Land and Nature section of the draft action plan includes only a small aspiration to curtail greenhouse gas emissions from animal farming. In Appendix 2.2 it states that a 24% reduction in grazing is needed. Given that eating sheep, cows or their secretions is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than any other source of food, it makes no sense to aim for such a small reduction. Furthermore, there is no action defined to achieve this reduction.

Why eliminating animal products from diets or, at least, making drastic reductions, is a cheap, quick and effective way to delay climate change

Let’s be clear. The Council’s Draft Climate Action Plan does NOT argue that eating plant-based or vegan food is expensive. That’s a claim often raised by others. Just like a diet based on animal products, there are cheap plant-based/vegan diets and there are more expensive ones too. A wholefood plant-based/vegan diet based around grains and pulses is, however, almost certainly going to be cheaper than a standard British diet. Regardless of the expense of any diet, changing it is cheaper than buying an electric car, investing in home insulation, installing a heat pump, investing in rooftop solar panels. It can also be achieved much more quickly.

If you read on, you’ll see how switching to a plant-based/vegan diet almost eliminates human-controlled emissions of methane, a very potent but short-lived greenhouse gas. Because it is quick and inexpensive to make such a change, it could buy time for the more difficult and costly sources of greenhouse gas emissions to be curtailed. That could be a life-saving benefit if the Harvard modelling mentioned above became a reality. In the UK, re-wilding land currently used for grazing and growing crops for animal feed would remove not ten but around twelve years of UK greenhouse gas emissions. Surely, that amounts to a huge justification for meaningful actions to be instigated as soon as possible through Calderdale’s Draft Climate Action Plan.

A longer read: misleading data could be a reason why dietary change is given a low priority in Calderdale’s Draft Climate Action Plan

Animal farming accounts for between 18.5% and 35% of global greenhouse gas emissions. (The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s 14.5% estimate has been discredited.) It therefore seems obvious that a drastic reduction or elimination of meat, dairy, eggs, fish and other animal product consumption should be given a high priority in Calderdale’s Draft Climate Action Plan. However, there are deficiencies in the data for animal farming’s greenhouse gas emissions as they relate to Calderdale. This is probably the main reason why dietary change has been given a low priority in the plan. There are two ways that the Calderdale data are deficient:

- Much of the food consumed in Calderdale is produced elsewhere and international greenhouse gas accounting rules dictate that emissions are attributed to the producer of a product and not to the consumer even though climate change recognises no national borders. In addition to some of Calderdale’s food-related greenhouse gas emissions being attributed to other parts of the UK, it has been estimated that 75% of all of the UK’s food-related environmental impacts arise beyond UK borders.

- The Calderdale data also exclude the greenhouse gas emissions associated with food-related transport, energy supply, fertiliser manufacture, land-use change, bottom trawling, fish farming, animal feed, deforestation and forest fires abroad. Again, this deficiency is the product of international greenhouse gas accounting rules.

There is a third reason why animal farming’s impact on climate change is underemphasised for Calderdale, and the rest of the world too. It is the result of how the greenhouse gas methane is accounted for. The biggest human-induced source of methane emissions across Europe, including the UK, is animal farming. It arises from the digestive systems of ruminants (cows, sheep, goats) and also from the manure of all farmed animals. The other main human-induced sources of methane emissions are leaks from the oil and gas industry and also the waste industry but neither eclipses animal farming. Not even globally.

Methane decays in the atmosphere in around 20 years and so, unlike carbon dioxide, it does not accumulate over centuries. However, before it breaks down, it’s over 84-87 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than the carbon dioxide emissions associated with transportation, heating, cooling, industrial energy use etc.. Despite this high potency, methane’s impact is diluted in the data used to compare different activities and sources of greenhouse gas emissions. This is because the ‘global warming potential’ of each greenhouse gas is evened out over 100 years so that it can be compared with carbon dioxide. That is a convention with some logic when humanity keeps pumping methane into the atmosphere for the next 100 years but it underplays the benefits of cutting it.

The data that Calderdale has relied upon to prioritise its Draft Climate Action Plan are based on methane emissions being attributed an impact of only 28 times more than carbon dioxide’s over 100 years and not the 84-87 times more over 20 years. Given that there are only 18 years left for Calderdale to reach its net zero target by 2038, a 100 year timeframe is surely the wrong metric even though it is the norm.

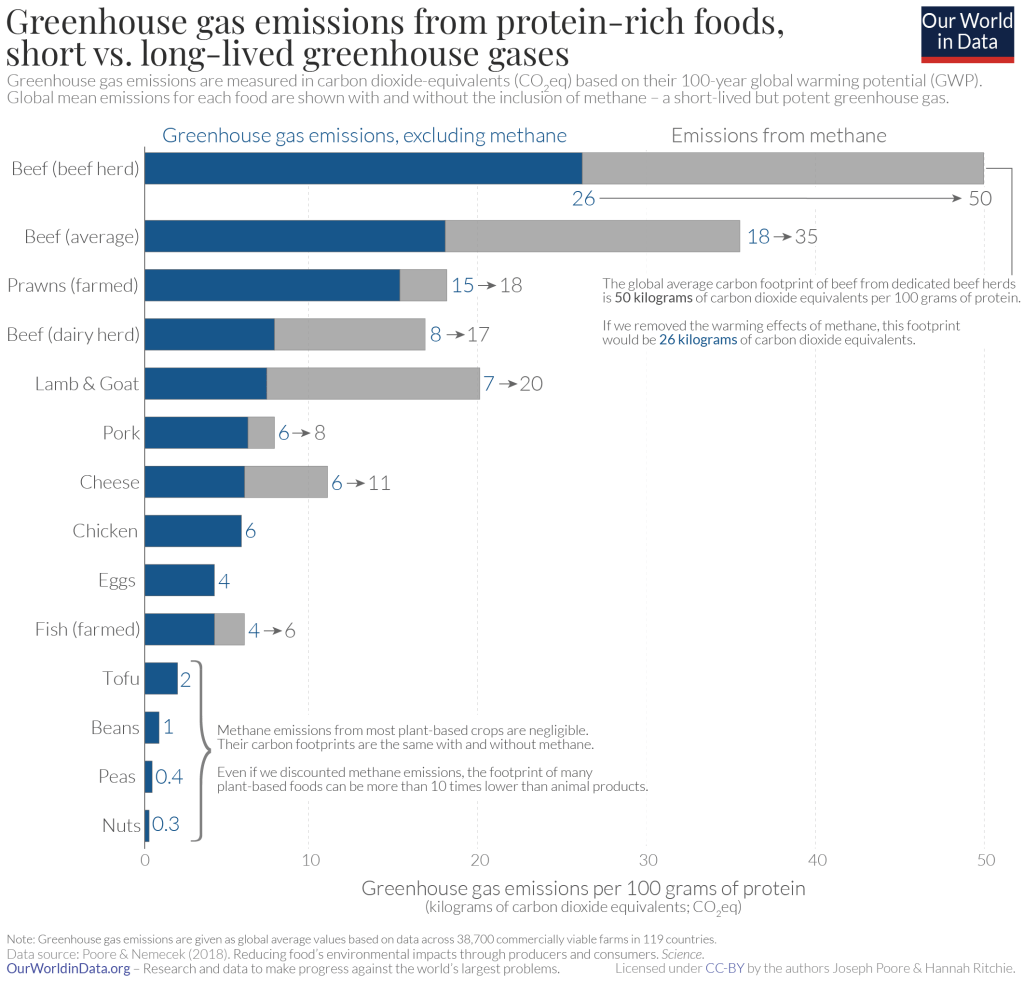

The diagram below provides a comparison between the global greenhouse gas emissions per 100 grams of protein from animal and plant sources. Like Calderdale, it utilises the 100-year global warming potential for the different greenhouse gases associated with food production. Crucially, it identifies methane emissions separately in grey and also that animal products are the only sources of protein that cause methane emissions. (Rice growing also produces methane but at a much lower level than animal products.) If the diagram were redrawn using a 20-year global warming potential for methane, the blue bars would remain about the same length but the grey bars would have to be around three times longer. Calderdale should therefore re-prioritise its action plan to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2038. Of course, it could continue relying on 100-year global warming potentials to measure its performance against the target but that wouldn’t be a genuine way to tackle climate change.

Whilst the emissions data for Calderdale food consumption are significantly under-estimated and therefore misleading, page 15 of Calderdale’s Draft Climate Action Plan goes some way to recognising this by committing to develop better data and improving clarity on what are referred to as ‘indirect carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions.’ It is therefore a serious omission that there is no related action included in the action plan schedule in Appendix 1.

Although the derivation of consumption-related greenhouse gas emissions data covering the full supply chain is not under Council influence, its absence should not delay action to make big cuts in the greenhouse gas emissions associated with diet. In the emergency we are facing, there is no time to waste in setting serious local targets and actions on dietary change.

For more on this subject, you might also like to read this recent article by George Monbiot: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/nov/09/leaders-cop27-livestock-farming-carbon-budget-governments

Please bear in mind that the data Monbiot presents on animal farming’s contribution to climate change are based on the convention that methane’s impact is equated to carbon dioxide’s over 100 years. The scale of the problem is therefore even bigger than he indicates.